Page 12 <previous page > <next page>

SOME HEALTH & SCIENCE NEWS

1. OFA BLADDER/KIDNEY STONE SURVEY

2. DOG FLU AND PARVO TREATMENT OPTIONS

3. GROWTH PLATES

If you or someone you know has owned a Basenji diagnosed with bladder/kidney stones,

please complete the simple survey available at the OFA website:

https://www.ofa.org/about/educational-resources/health-surveys

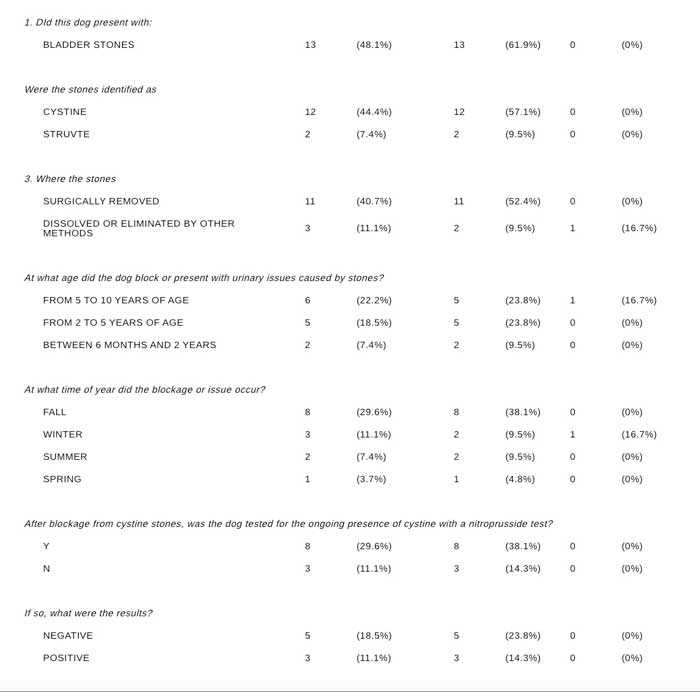

Here's some of the survey results:

You may have heard in the past that Tamiflu has been used to treat viruses and assume the use applies to canine flu. We have not heard of any instances of veterinarians officially prescribing the human use approved Tamiflu to dogs for flu symptoms. The majority of the discussion surrounded use of oseltamivir for parvovirus.

First, we should step back and look at the law. The Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act gives veterinarians the right to prescribe these human medications but with limitations. Part of the law is, “limited to circumstances when the health of an animal is threatened, or suffering or death may result from failure to treat.” In this instance, the use of oseltamivir would apply to parvovirus, as it is deadly. Canine flu would not fall under this category because dogs very rarely die directly from the canine flu viruses (H3N2 and H3N8). Only 2-3% of dogs that are immunocompromised or harbor Streptococcus bacteria in their pulmonary system and then develop a secondary bacterial pneumonia could can pass away. In case pneumonia does develop, antibiotics would be prescribed.

Canine influenza viruses can be spread by direct contact with aerosolized respiratory secretions from infected dogs, by contact with contaminated objects, and by people moving between infected and uninfected dogs. They are highly contagious, like human flu viruses. The signs of this illness in dogs are cough, runny nose, high fever, lethargy, eye discharge, and reduced appetite, but many dogs show only minor or no signs of illness. These cough symptoms differ from those of the common kennel cough complex as it does not initially produce a fever, unless secondary pneumonia occurs 7-10 days later.

Canine Parvovirus is ubiquitous and is spread through dog feces; it can live in the environment for months. The general symptoms are lethargy, severe vomiting, loss of appetite and bloody, foul-smelling diarrhea that can lead to life-threatening dehydration.

Parvovirus is a tricky disease to treat, but veterinarians have an arsenal of options to stave off death such as fluid replacement therapy, fresh-frozen plasma transfusions, whole blood transfusions, antiemetics for nausea and vomiting, possibly antibiotics for any secondary bacterial infection, antiparasitic medications for intestinal worms and oseltamivir depending on the severity of the disease.

So, how does oseltamivir (Tamiflu) work against parvovirus?

Oseltamivir inhibits the neurominidase enzyme, which is necessary for pathogenic bacteria to adhere to the intestinal endothelium and then penetrate into the bloodstream – a very important step in the progression of parvovirus. While this treatment option needs further study and may not be available due to stockpiling Tamiflu for human use, an Auburn University research team found that dogs treated with oseltamivir had increased weight gain and 100% survival rate versus the control group that experienced weight loss and an 81% survival rate. While the researchers could not establish a clear advantage to use oseltamivir, they did note that no adverse effects were associated with its use.

The absolute best parvo prevention of course is appropriate vaccination. Dr. Dodds’ protocol calls for parvovirus and distemper vaccinations at 9-10 and 14-15 weeks of age, plus a third parvo booster at 18 weeks of age. Titer testing is then measured a year later followed by re-titering every three years thereafter.

So, what are the treatment options for canine flu?

As mentioned, Tamiflu would not be approved for use for canine influenza unless, potentially, a highly virulent, deadly strain developed or if a strain jumped the species barrier to humans. Regarding human influenza, Tamiflu is prescribed for human use after signs of influenza are present and depending on the strain. We could not find any mention of similarly used drugs in current development for canine influenza.

The two known canine influenza strains in North America are H3N2 and H3N8. Vaccines are available for both. While we definitely promote the use of parvovirus vaccine, we do not currently recommend the routine use of the canine influenza vaccines.

Why we say no to canine influenza vaccine:

Canine flu, like human flu, is self-limiting and usually resolves itself after 1-2 weeks.

The mortality rate amongst dogs is less than 5-10% and more than likely occurs due to a secondary bacterial infection like pneumonia.

Companion animal influenza vaccines are often not adapted for mutations after initial development. In 2012, Pfizer Animal Health released a study it funded of its H3N8 vaccine which was isolated from dogs in Iowa in 2005. The researchers found that the Iowa vaccine was effective against more recent strains isolated from other parts of the country. However, the researchers noted, “The greatest amount of divergence correlated with the more recent isolates.“

Naturally generated immunity is better than strain-specific vaccine immunity. In 2008, a groundbreaking study was released about the 1918 human flu pandemic. Eric Altschuler and a team of researchers gathered 32 survivors who were born before 1915. 94% of them (30 people) had produced antibodies that neutralized the 1918 flu virus. The scientists went further and found out that the gene sequence that encoded these antibodies had accumulated many mutations, which suggests that the cells had made further adaptations to similar viruses after 1918. This means they would more than likely not become ill if the 1918 virus cropped up again.

If my dog gets the flu, what can I do?

We all want quick fixes to make our companion dogs feel better. However, medications are not generally given beyond supportive care unless a secondary bacterial infection or high fever develop.

The American Veterinary Medical Association and the FDA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call for supportive care, which involves keeping your dog hydrated and comfortable while the body mounts an immune response to the infection to facilitate recovery. If a high fever develops, ask your veterinarian about treatment options. Good husbandry and nutrition may also help dogs mount an effective immune response.

W. Jean Dodds, DVM

Hemopet / NutriScan

11561 Salinaz Avenue

Garden Grove, CA 92843

Growth Plates

Young puppy. Long way to go before the growth plates close. Be careful.